Learning Goals

- Refresh and organize students’ existing knowledge on Git (learn how to learn more).

- Students can explain difference between merge and rebase and when to use what.

- How to use Git workflows to organize research software development in a team.

- Get to know a few useful GitHub/GitLab standards and a few helpful tools.

- Get to know a few rules on good commit messages.

Material is taken and modified from the SSE lecture, which builds partly on the py-rse book.

1. Introduction to Version Control

Why Do We Need Version Control?

Version control …

- tracks changes to files and helps people share those changes with each other.

- Could also be done via email / Google Docs / …, but not as accurately and efficiently

- was originally developed for software development, but today cornerstone of reproducible research

“If you can’t git diff a file format, it’s broken.”

How Does Version Control Work?

- master (or main) copy of code in repository, can’t edit directly

- Instead: check out a working copy of code, edit, commit changes back

- Repository records complete revision history

- You can go back in time

- It’s clear who did what when

The Alternative: A Story Told in File Names

http://phdcomics.com/comics/archive/phd052810s.gif

A Very Short History of Version Control I

The old centralized variants:

- 1982: RCS (Revision Control System), operates on single files

- 1986 (release in 1990): CVS (Concurrent Versions System), front end of RCS, operates on whole projects

- 1994: VSS (Microsoft Visual SourceSafe)

- 2000: SVN (Apache Subversion), mostly compatible successor of CVS, still used today

A Very Short History of Version Control II

Distributed version control:

- Besides remote master version, also local copy of repository

- More memory required, but much better performance

- For a long time: highly fragmented market

- 2000: BitKeeper (originally proprietary software)

- 2005: Mercurial

- 2005: Git

- A few more

Learn more: Podcast All Things Git: History of VC

The Only Standard Today: Git

No longer a fragmented market, there is nearly only Git today:

- Stackoverflow developer survey 2021: > “Over 90% of respondents use Git, suggesting that it is a fundamental tool to being a developer.”

- Is this good or bad?

More Facts on Git

- Git itself is open-source: GPL license

- Source code on GitHub, contributions are a bit more complicated than a simple PR

- Written mainly in C

- Started by Linus Torvalds, core maintainer since later 2005: Junio Hamano

- Git (the version control software) vs. git (the command line interface)

Forges

There is a difference between Git and hosting services (forges):

- GitHub

- GitLab, open-source, hosted e.g. at IPVS

- Bitbucket

- SourceForge

- many more

- often, more than just hosting, also DevOps

2. Recap of Git Basics

Expert level poll

Which level do you have?

- Beginner: hardly ever used Git

- User: pull, commit, push, status, diff

- Developer: fork, branch, merge, checkout

- Maintainer: rebase, squash, cherry-pick, bisect

- Owner: submodules

Overview

Git overview picture from py-rse

Demo

git --help,git commit --helpincomplete statement

git commThere is not the one solution how to do things with Git. I simply show what I typically use.

Don’t use a client if you don’t understand the command line

git- Look at GitHub

- preCICE repository

- default branch

develop - fork -> my fork

- Working directory:

- ZSH shell shows git branches

git remote -v(I have upstream, myfork, …)- mention difference between ssh and https (also see GitHub)

- get newest changes

git pull upstream develop git log-> I use special format, see~/.gitconfig,- check log on GitHub; explain short hash

git branchgit branch add-demo-featuregit checkout add-demo-feature

- First commit

git status-> always tells you what you can dovi src/action/Action.hpp-> add#include "MagicHeader.hpp"git diff,git diff src/com/Action.hpp,git diff --color-wordsgit status,git add,git statusgit commit-> “Include MagicHeader in Action.hpp”git status,git log,git log -p,git show

- Change or revert things

- I forgot to add sth:

git reset --soft HEAD~1,git status git diff,git diff HEADbecause already stagedgit loggit commit- actually all that is nonsense:

git reset --hard HEAD~1 - modify again, all nonsense before committing:

git checkout src/action/Action.hpp

- Stash

- while working on unfinished feature, I need to change / test this other thing quickly, too lazy for commits / branches

git stashgit stash pop

- Create PR

- create commit again

- preview what will be in PR:

git diff develop..add-demo-feature git push -u myfork add-demo-feature-> copy link- explain PR template

- explain target branch

- explain “Allow edits by maintainers”

- cancel

- my fork -> branches -> delete

- Check out someone else’s work

- have a look at an existing PR, look at all tabs, show suggestion feature

- but sometimes we want to really build and try sth out …

git remote -vgit remote add alex git@github.com:ajaust/precice.gitif I don’t have remote already (or somebody else)git fetch alexgit checkout -t alex/[branch-name]- I could now also push to

ajaust’s remote

Useful Links

- Official documentation

- Video: Git in 15 minutes: basics, branching, no remote

- Chapters 6 and 7 of Research Software Engineering with Python

- Podcast All Things Git: History of VC

- git purr

3. Merge vs. Rebase

Linear History

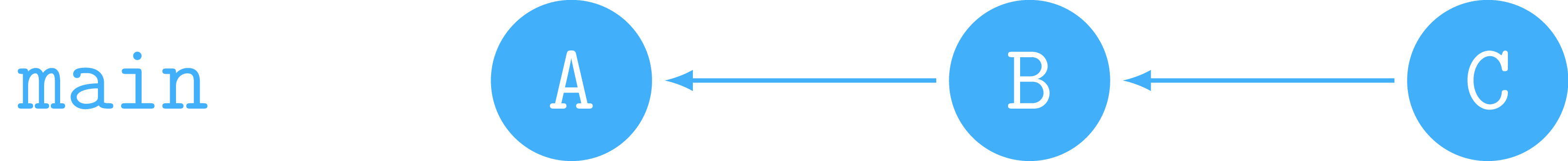

- Commits are snapshots + pointer to parent, not diffs

- But for linear history, this makes no difference

- Each normal commit has one parent commit

c05f017^<–c05f017A=B^<–B- (

^is the same as~1) - Pointer to parent commit goes into hash

git showgives diff of commit to parent

Merge Commits

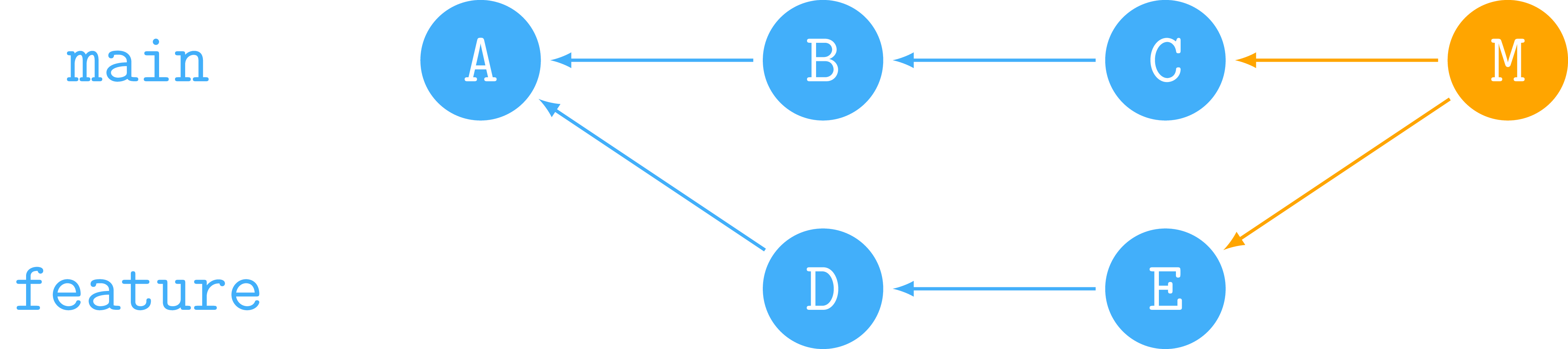

git checkout main && git merge feature

- A merge commit (normally) has two parent commits

M^1andM^2(don’t confuse^2with~2)- Can’t show unique diff

- First parent relative to the branch you are on (

M^1=C,M^2=E)

git showgit show: “combined diff”- GitHub:

git show --first-parent git show -m: separate diff to all parents

Why is a Linear History Important?

We use here:

Linear history := no merge commits

- Merge commits are hard to understand per se.

- A merge takes all commits from

featuretomain(ongit log). –> Hard to understand - Developers often follow projects by reading commits (reading the diffs). –> Harder to read (where happened what)

- Tracing bugs easier with linear history (see

git bisect)- Example: We know a bug was introduced between

v1.3andv1.4.

- Example: We know a bug was introduced between

How to get a Linear History?

- Real conflicts are very rare in real projects, most merge commits are false positives (not conflicts) and should be avoided.

- If there are no changes on

main,git mergedoes a “fast-forward” merge (no merge commit). - If there are changes on

main, rebasefeaturebranch.

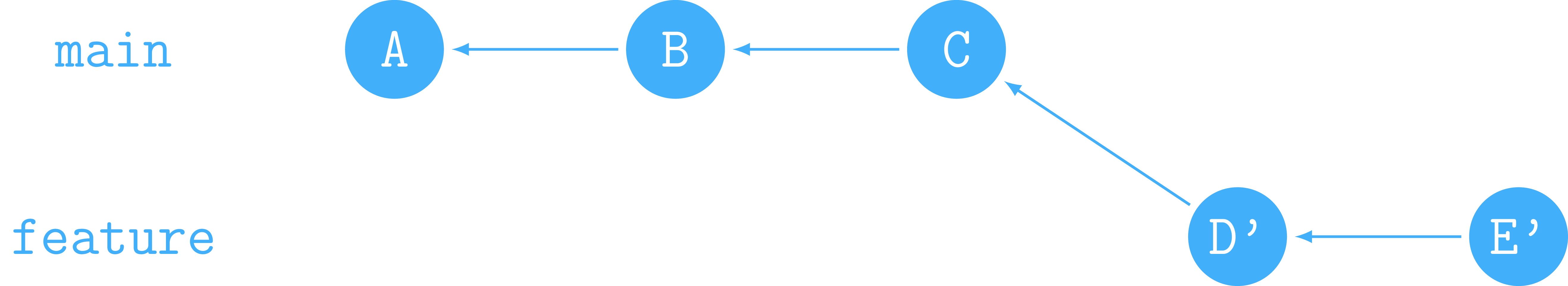

Rebase

git checkout feature && git rebase main

- States of issues change (and new parents) –> history is rewritten

- If

featureis already on remote, it needs a force pushgit push --force myfork feature(or--force-with-lease). - Be careful: Only use rebase if only you work on a branch (a local branch or a branch on your fork).

- For local branches very helpful:

git pull --rebase(fetch & rebase)

GitHub PR Merge Variants

- GitHub offers three ways to merge a non-conflicting (no changes in same files) PR:

- Create a merge commit

- Squash and merge

- Rebase and merge

- Look at a PR together, e.g. PR 1432 from preCICE (will be closed eventually)

What do the options do?

Squash and Merge

- … squashes all commits into one

- Often, single commits of feature branch are important while developing the feature,

- … but not when the feature is merged

- Works well for small feature PRs

- … also does a rebase (interactively,

git rebase -i)

Conflicts

But what if there is a conflict?

- Resolve by rebasing

featurebranch (recommended) - Or resolve by merging

mainintofeature

Summary and Remarks

- Try to keep a linear history with rebasing whenever reasonable

- Don’t use rebase on a public/shared branch during development

- Squash before merging if reasonable

- Delete

featurebranch after merging - Local view:

git log --graph - Remote view on GitHub, e.g. for preCICE

Further Reading

- Bitbucket docs: “Merging vs. Rebasing”

- Hackernoon: “What’s the diff?”

- GitHub Blog: “Commits are snapshots, not diffs”

- Stack Overflow: “Git show of a merge commit”

4. Working in Teams / Git Workflows

Why Workflows?

- Git offers a lot of flexibility in managing changes.

- When working in a team, some agreements need to be made however (especially on how to work with branches).

Which Workflow?

- There are standard solutions.

- It depends on the size of the team.

- Workflow should enhance effectiveness of team, not be a burden that limits productivity.

Centralized Workflow

- Only one branch: the

mainbranch - Keep your changes in local commits till some feature is ready

- If ready, directly push to

main; no PRs, no reviews - Conflicts: fix locally (push not allowed anyway), use

git pull --rebase - Good for: small teams, small projects, projects that are anyway reviewed over and over again

- Example: LaTeX papers

- Put each section in separate file

- Put each sentence in separate line

Feature Branch Workflow

- Each feature (or bugfix) in separate branch

- Push feature branch to remote, use descriptive name

- e.g. issue number in name if each branch closes one issue

mainshould never contain broken code- Protect direct push to

main - PR (or MR) with review to merge from feature branch to

main - Rebase feature branch on

mainif necessary - Delete remote branch once merged and no longer needed (one click on GitHub after merge)

- Good for: small teams, small projects, prototyping, websites (continuous deployment), documentation

- Aka. trunk-based development or GitHub flow

Gitflow

- Visualization by Vincent Driessen, from original blog post in 2010

mainanddevelopmaincontains releases as tagsdevelopcontains latest features

- Feature branches created of

develop, PRs back todevelop - Protect

mainand (possibly)developfrom direct pushes - Dedicated release branches (e.g.,

v1.0) created ofdevelop- Tested, fixed, merged to

main - Afterwards, tagged, merged back to

develop

- Tested, fixed, merged to

- Hotfix branches directly of and to

main - Good for: software with users, larger teams

- There is a tool

git-flow, a wrapper aroundgit, e.g.git flow init… but not really necessary IMHO

Forking Workflow

- Gitflow + feature branches on other forks

- More control over access rights, distinguish between maintainers and external contributors

- Should maintainers also use branches on their forks?

- Makes overview of branches easier

- Distinguishes between prototype branches (on fork, no PR), serious enhancements (on fork with PR), joint enhancements (on upstream)

- Good for: open-source projects with external contributions (used more or less in preCICE)

Do Small PRs

- For all workflows, it is better to do small PRs

- Easier to review

- Faster to merge –> fewer conflicts

- Easier to squash

Quick Reads

- Atlassian docs on workflows

- Original gitflow blog post

- Trunk-based development

- GitHub flow

- How to keep pull requests manageable

5. GitHub / GitLab Standards

What Do We Mean With Standards?

- GitHub uses standards or conventions.

- Certain files or names trigger certain behavior automatically.

- Many are supported by most forges.

- This is good.

- Everybody should know them.

Special Files

Certain files lead to special formatting (normally directly at root of repo):

README.md- … contains meta information / overview / first steps of software.

- … gets rendered on landing page (and in every folder).

LICENSE- … contains software license.

- … gets rendered on right sidebar, when clicking on license, and on repo preview.

CONTRIBUTING.md- … contains guidelines for contributing.

- First-time contributors see banner.

CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md- … contains code of conduct.

- … gets rendered on right sidebar.

Issues and PRs

- Templates for description in

.githubfolder closes #34(or several other keywords:fixes,resolves) in commit message or PR description will close issue 34 when merged.help wantedlabel gets rendered on repo preview (e.g. “3 issues need help”).

6. Commit Messages

Commit Messages (1/2)

- Consistent

- Descriptive and concise (such that complete history becomes skimmable)

- Explain the “why” (the “how” is covered in the diff)

Commit Messages (2/2)

The seven rules of a great Git commit message:

- Separate subject from body with a blank line.

- Limit the subject line to 50 characters.

- Capitalize the subject line.

- Do not end the subject line with a period.

- Use the imperative mood in the subject line.

- Wrap the body at 72 characters.

- Use the body to explain what and why vs. how.